Share Video:

D & E Abortion

Second Trimester

A dilation (dilatation) and evacuation abortion, D&E, is a surgical abortion procedure during which an abortionist first dilates the woman’s cervix and then uses instruments to dismember and extract the baby from the uterus. The D&E abortion procedure is usually performed between thirteen and twenty-four weeks LMP (that is thirteen to twenty-four weeks after the first day of the woman’s last menstrual period).

To prepare for a D&E abortion, the abortionist uses laminaria, a form of sterilized seaweed, to open the woman’s cervix 24 to 48 hours before the procedure. The laminaria soaks up liquid from the woman’s body and expands, widening (i.e., dilating) the cervix.

When the woman returns to the abortion clinic, the abortionist may administer anesthesia and further open the cervix using metal dilators and a speculum. The abortionist inserts a large suction catheter into the uterus and turns it on, emptying the amniotic fluid.

After the amniotic fluid is removed, the abortionist uses a sopher clamp — a grasping instrument with rows of sharp “teeth” — to grasp and pull the baby’s arms and legs, tearing the limbs from the child’s body. The abortionist continues to grasp intestines, spine, heart, lungs, and any other limbs or body parts. The most difficult part of the procedure is usually finding, grasping and crushing the baby’s head. After removing pieces of the child’s skull, the abortionist uses a curette to scrape the uterus and remove the placenta and any remaining parts of the baby.

The abortionist then collects all of the baby’s parts and reassembles them to make sure there are two arms, two legs, and that all of the pieces have been removed.

If a woman has been dilated with laminaria, but not yet undergone the surgical abortion, she can still change her mind. Depending on how much her cervix has dilated, there is a potential risk of miscarriage as dilation continues because her body may begin contractions and labor. A woman who changes her mind should immediately contact a medical professional to ensure the laminaria is properly removed.1

- Kaufman, K. The Abortion Resource Handbook.” New York: Fireside, 1997, 32, 153. <https://books.google.com/books?id=F7q3TB6_koYC&pg=PR18&dq=the+abortion+resource+handbook&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjBpZvBxNrJAhUO42MKHchnCA4Q6AEIJjAA#v=onepage&q=the%20abortion%20resource%20handbook&f=false>.

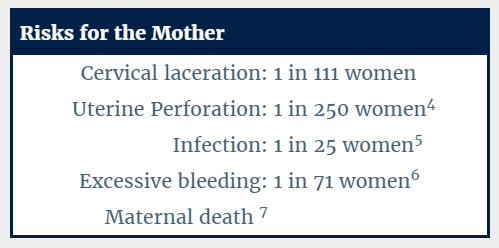

For the woman, this procedure carries a significant immediate risk of major complications. Since the baby is removed in pieces, sharp pieces of broken fetal bones can puncture the woman’s uterus or cause a large tear (laceration). This perforation or laceration of the uterus or cervix, can also possibly damage the bowel, bladder, the rectum and other maternal organs.

In addition to perforation and damage to internal organs, a second trimester abortion has a greatly increased risk of excessive bleeding and hemorrhaging. This is because the placenta is tightly adherent to the lining of the womb at this stage in pregnancy, and removing it often requires considerable scraping. The risk of excessive bleeding as a result of the abortion increases as the baby develops. The woman may also experience extreme blood loss if her uterus or cervix is injured, if the uterus does not contract properly after the procedure, or if she has an incomplete abortion. She also runs a higher risk of cervical damage, uterine perforation and scarred tissue, which may result in future pregnancy complications, such as miscarriage and preterm birth.1 Uterine rupture can even lead to maternal death.

Long-term damage from second trimester abortion is more frequent than for abortions in the first trimester. Because the cervix has to be so widely dilated to extract the larger child, the risk of cervical damage is much greater, increasing the risk that a woman will be unable to carry a future pregnancy to term. The CDC also estimates that the risk of death increases by 38% for each additional week of gestation.2

There are studies that indicate the risk of depression, anxiety, and suicide is greater for a woman who aborts an unwanted pregnancy than it is for a woman who carries an unwanted pregnancy to term.3

- Lohr, Patricia A. “Surgical Abortion in Second Trimester”, Reproductive Health Matters, May 2008, 156. <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18772096>.

- Bartlett, Linda A., et al. “Risk Factors for Legal Induced Abortion–Related Mortality in the United States.” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 103, No. 4, April 2004, pp. 729-737. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15051566>.

- Fergusson, David M with Joseph M. Boden and L. John Harwood. “Does abortion reduce the mental health risks of unwanted or unintended pregnancy? A re-appraisal of the evidence.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Sept. 2013, Vol. 47, No. 9, pp. 819-827. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23553240>.

- Fox, Michelle C. and Jennifer L. Hayes. “Cervical Dilation in Second-Trimester Abortion.” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol. 52, Issue 2, June 2009, pp. 172-8 <http://journals.lww.com/clinicalobgyn/Abstract/2009/06000/Cervical_Dilation_in_Second_Trimester_Abortion.8.aspx>.

- Cates, Willard Jr. and David A. Grimes. “Deaths from Second Trimester Abortion by Dilatation and Evacuation: Causes, Prevention, Facilities.” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 58, Issue 4, October, 1981. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7279335>.

- Peterson, W.F., et al. “Second-Trimester Abortion by Dilatation and Evacuation: An Analysis of 11,747 Cases.” Volume 2, No. 2, Aug 1983. <https://venus.ipas.org/library/fulltext/PetersonOG1983.pdf>.

- “Risk Factors for Legal Induced Abortion-Related Mortality in the United States.” American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol 103, No. 4, April 2004.

While some states have enacted prohibitions on abortion — including restricting the procedure after a certain point in pregnancy — other states permit abortions without exception.

Week 13

At week thirteen LMP, the preborn baby’s fingerprints are visible, and the child’s organs are visible through his or her thin skin. The baby is roughly three inches long during this stage of pregnancy. Source: Baby Center.

Week 16

At week sixteen LMP, the child’s toenails begin to form, and his or her face and limbs are much more developed. The baby’s heart is pumping roughly 25 quarts of blood every day, and will continue as the child develops in the womb. Many mothers feel the baby move by this point in the pregnancy. Source: Baby Center.

Week 20

At twenty weeks LMP, the child’s nervous system is developed enough to feel pain. Research by the University of Toronto shows that babies at this stage can feel pain in the womb — even with greater intensity than adults. Almost all mothers feel the baby move by this point in pregnancy. Source: Baby Center.

Week 24

At twenty-four weeks LMP, the baby is roughly a foot long, and his or her brain is developing rapidly. The child’s lungs are also developing into their branch-like structure. At this age, almost all babies can survive outside the mother if given proper support. Source: Baby Center.

Please note: This website has been researched and reviewed by physicians for medical accuracy; however, it is not intended to constitute medical advice or replace the individualized counsel of a doctor.